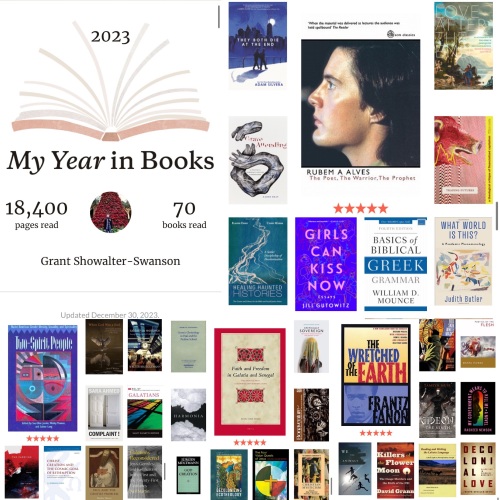

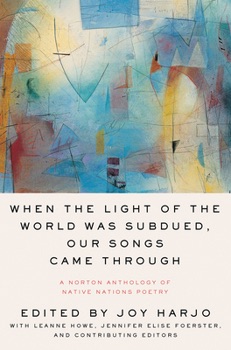

1. When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry, edited by Joy Harjo, with LeAnne Howe and Jennifer Elise Foerster

2. Poet, the Warrior, the Prophet, by Rubem Alves

3. Decolonial Christianities: Latinx and Latin American Perspectives, edited by Raimundo Barreto and Roberto Sirvent

4. Reading and Writing the Lakota Language, by Albert White Hat Sr.

5. Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization, by Elaine Enns and Ched Myers

6. Galatians: A Theological Commentary on the Bible, by Nancy Elizabeth Bedford

7. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, by Linda Tuhiwai Smith

8. Complaint!, by Sara Ahmed

9. Faith and Freedom in Galatia and Senegal: The Apostle Paul, Colonists and Sending Gods, by Aliou Cissé Niang

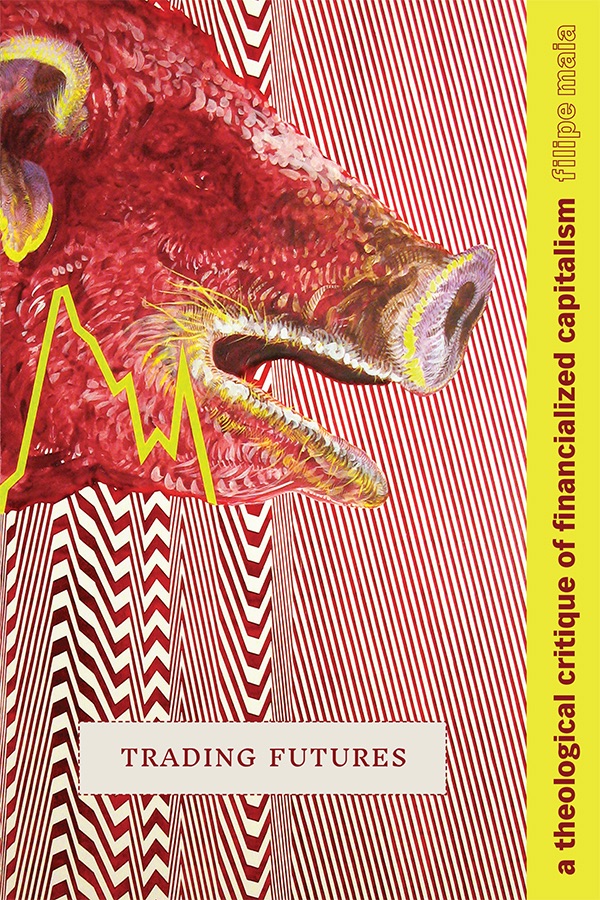

10. Trading Futures: A Theological Critique of Financialized Capitalism, by Filipe Maia